Using Oceanography to Help North Atlantic Right Whales

Off the coast of South Jersey, lucky whale watchers may sometimes glimpse a critically endangered North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis). Despite protections in the United States (US) from whaling since 19351, this baleen whale species has struggled to recover, with only about 340 individuals remaining in the world2 . Although most right whales summer off of Maine and Canada and travel to Georgia and Florida during the winters, not all of them migrate every year, meaning that individual right whales can be found all along the east coast of the US during most of the year3. Beyond the normal challenges of trying to study a marine animal (lack of light and GPS signal underwater for starters!), right whales are moving. They have abandoned some of the habitats they traditionally use during some parts of the year, and are taking up residency in previously unused spots.

One of these new year-round habitats is located south of Nantucket Island off of Massachusetts4. Researchers at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium, who noticed the shift during aerial surveys, partnered with Rutgers University to try to understand what was going on. And I was the graduate student who tackled this mystery in my thesis.

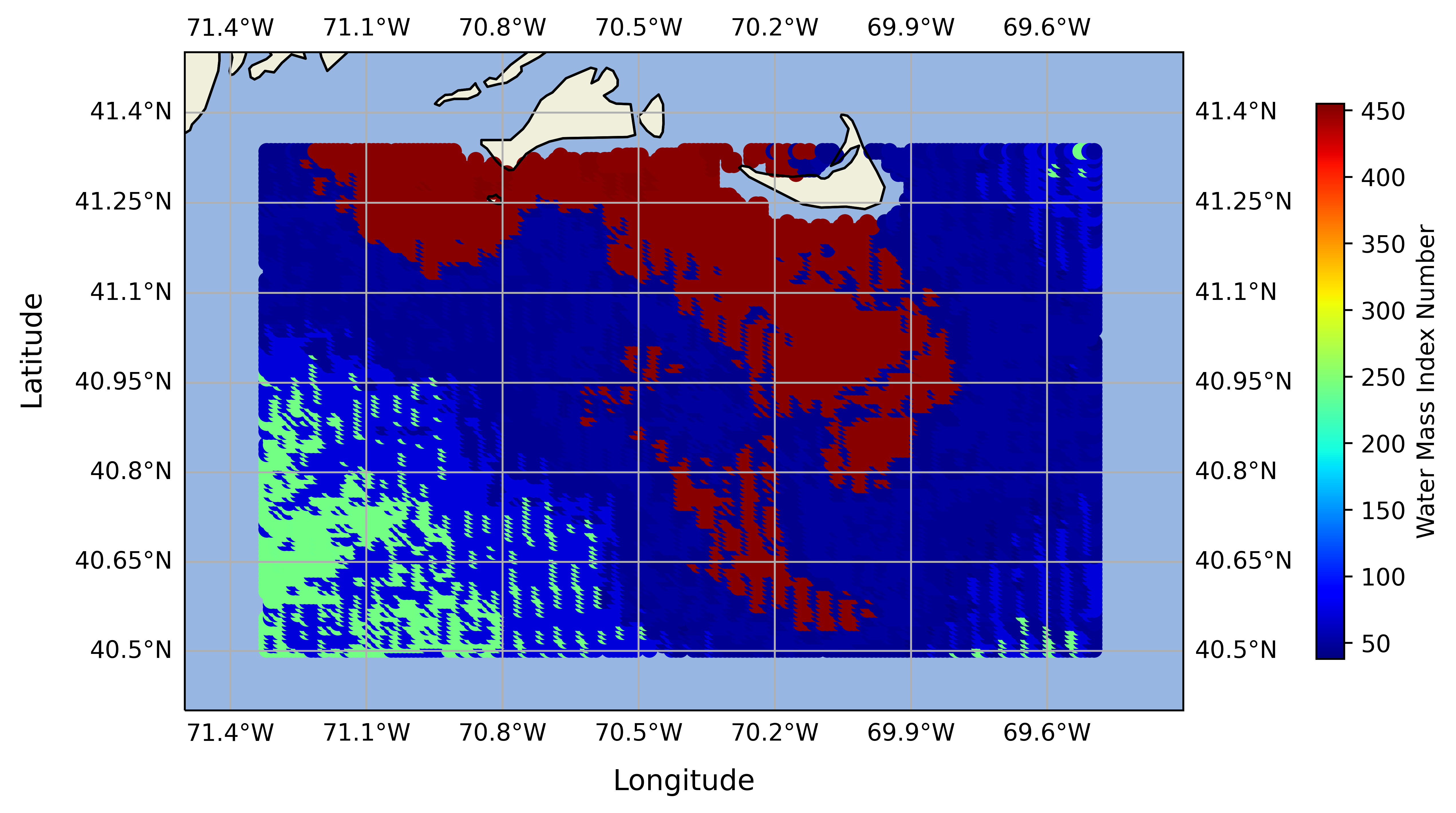

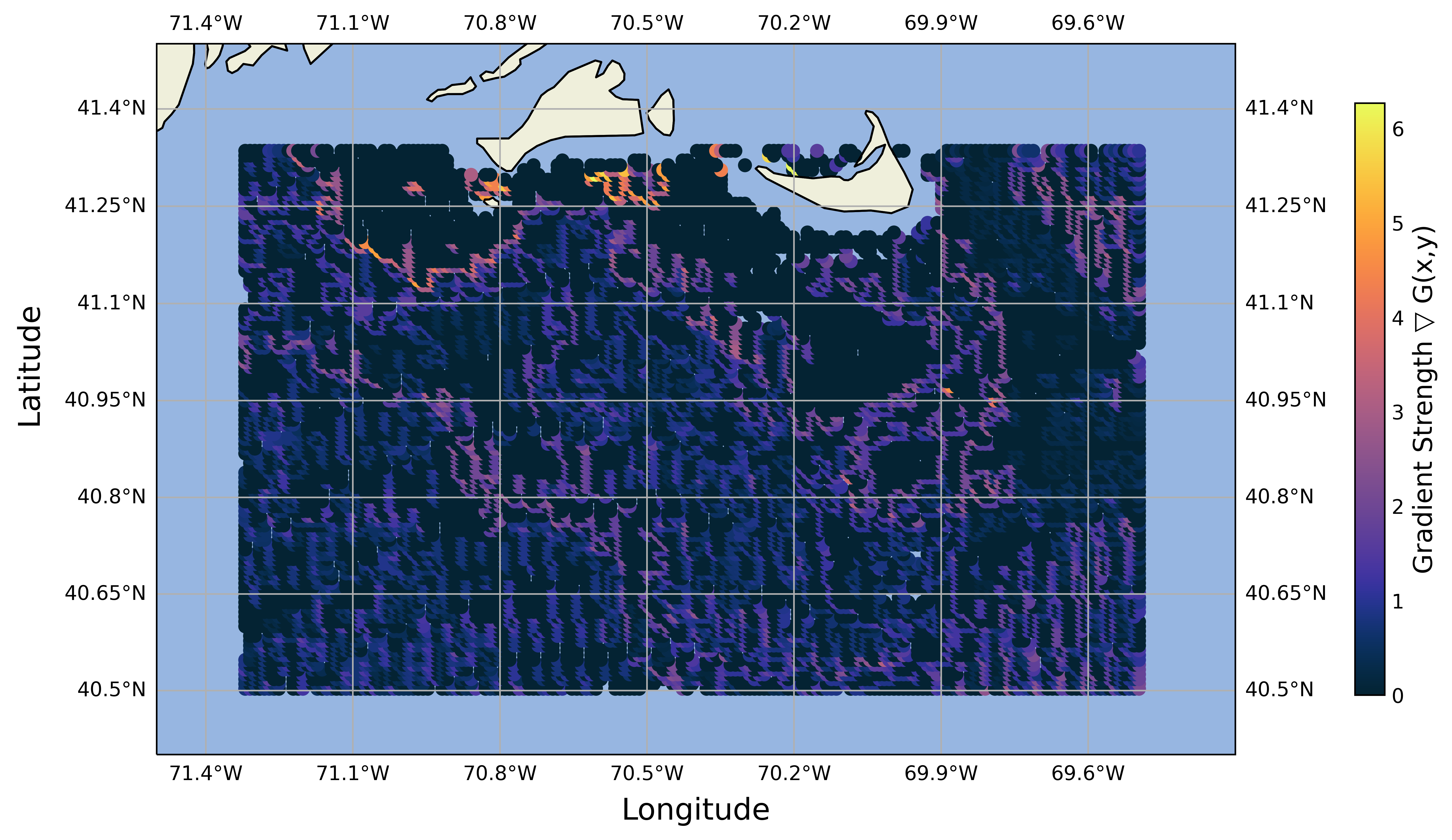

We used a data product from the University of Delaware, which combines sea surface temperature and ocean color, measured via satellite, to define distinct ocean masses, or bodies, within the ocean5. Sea surface temperature has undergone dramatic changes due to climate change. Ocean color measures how light reflects off the ocean at different wavelengths, and is connected to plankton concentrations- very useful considering that right whales eat tiny zooplankton called copepods. The figures below give an idea of these water masses: on the top, each color represents a different water

mass, and the map on the bottom shows the gradient (or how different one mass is from its neighbor) between the masses.